Fund Facts are extremely helpful. Investors should review them clearly, as they spell out key information about your mutual fund (or exchange-traded fund – ETF), including a brief discussion of how the fund invests, what are its top holdings, performance history, as well as how much you pay in fees each year to own the fund.

In Canada, a Fund Facts (or ETF Facts) is required before you purchase any of these investment vehicles. In the case of discount brokerages, this document is given to you immediately after your purchase.

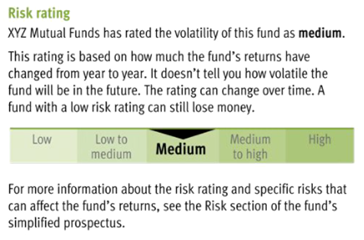

Another important piece of information in the document is the fund’s risk measurement. This is what this section of the fund fact sheet looks like:

Source: https://www.getsmarteraboutmoney.ca/tools/fund-facts-interactive-sample/

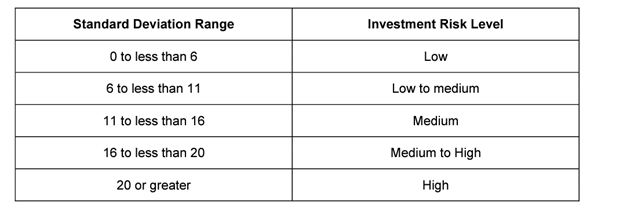

The intention of this rating is to give the investor a very broad idea of a fund’s historical risk level. Behind the scenes is a reasonably simple calculation, as stipulated by the Canadian Securities Administrators in their Orientation 2016. For those with mathematical inclinations, the “risk rating” listed in the Fund Facts is indeed a standard deviation of 10-year returns with a chart that translates to a level of investment risk or a risk rating:

Source: https://www.osc.ca/sites/default/files/pdfs/irps/ni_20161208_81-101-81-102_csa-mutual-fund-risk.pdf

Funds that have regular returns (such as money market funds) will have very little variation in returns, which translates to a lower level of risk, while equity funds move a lot more and will therefore have higher levels of risk. Although on paper it would seem like a good measure that investors should rely on when making investment decisions, it is not true. here’s why

Why the Fund Facts risk rating is not working

The calculation treats volatility in the positive direction (for example, if a fund rises 50% in one day) as it does in the negative direction (if a fund loses 50% in one day). This is no longer how most investors think about risk. Most investors would probably accept a fund’s value rising rapidly. They would like do not agree with the value of a fund fall rapidly. Standard deviation treats both sides of this coin equally.

The rating uses 10 years of monthly returns. Given that we are now in 2022, the calculation now excludes returns during the 2008-2009 financial crisis, which would be a litmus test for understanding how a fund manager endured a systemic market correction. Additionally, if we had calculated the risk rating using 15 years of data instead of 10, the results would be very different, as seen below:

The table above compares what a conceptual “risk rating” would be if we had used 15 years of monthly returns instead of 10 for all Canadian-domiciled mutual funds and ETFs with an inception date prior to the 1st April 2007. Here we can see that there are 451 funds that would today be classified as ‘low to medium’ risk in a Fund Facts. If we use 15 years of data instead, 156 of those funds would actually be rated “average.” In other words, using less data makes these funds less risky.

When a fund’s 10-year standard deviation crosses a threshold (say, 5.9 to 6.1), the rating itself changes (from “low” to “low to medium”). For the unaware investor, this could result in a pause when in reality the actual historical volatility has not materially changed. It happens more often than you might think. In a comment letter to IIROC and the MFDA last year, Morningstar also urged advisers not to rely on the risk rating for the same reason.

What our research revealed about Canadian mutual fund risk ratings

To create this study, we took the oldest share class of every mutual fund and ETF with at least 10 years of history in our Canadian database and calculated the risk rating as it would appear each July from 2015 to 2021. We then counted the number of times a risk rating changed according to CSA methodology.

Of the 62 money market funds that had a 10-year history, none of them changed risk ratings, which is intuitive.

However, when you look at allocation (i.e. balanced) funds, a good portion of them have changed their risk rating twice in the space of six years, which is concerning because the majority of Canadian assets are invested in balanced funds. It is very unlikely that 17% (69 out of 252) of balanced funds have changed their investment mandate twice in six years. It is also unlikely that 17% of balanced funds have actually become materially more or less risky in the space of six years. The concern also spills over to equity funds, which naturally show more volatility, but the fact that the majority of these funds change their risk rating frequently is not necessarily helpful for the investor.

How should investors view their risk levels?

Although the risk rating is flawed in many ways, it is still an objectively calculated measure, which in its own way is useful to some extent as long as investors understand the limitations.

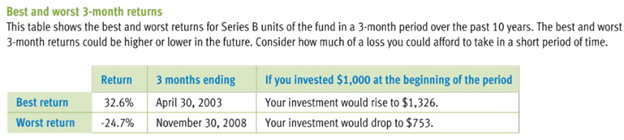

That said, there are other financial measures of risk that may be useful to use in place of the risk rating, one of which is shown directly in the Fund Facts:

A measure of the best/worst 3-month returns provides a much more relevant measure of the level of risk inherent in a fund. An investor may not know what an “average” level of risk is, but they can easily understand that they have lost 24% of their assets in the space of three months. That said, like the measure of risk, this 10-year retrospective of best/worst returns now rules out the financial crisis.

Related to this but do not shown in the Fund Facts is a metric called peak loss, which measures over a period of time how much a fund declines in value from its peak to its valley before a period of recovery. This is useful because it removes the time constraint. A fund can continue to fall for more than 3 months at a time.

That said, remember that if you own more than one mutual fund or ETF (which most investors do), the risk rating displayed on a fund fact sheet becomes less relevant because it what matters is the globally risk in your portfolio. In other words, the performance (and risk) of your portfolio is not simply an “average” of the individual risk levels of the component funds. Instead, overall risk is calculated by taking into account correlations between funds, which are not considered when looking at individual fund risk ratings. Your advisors’ primary responsibility when making investment recommendations is to ensure that a fund (in the context of your overall portfolio) is within your risk tolerance and risk capacity.

Pro Tip: Investors looking to dig deeper can look at metrics such as the Sortino and Treynor ratios, which are performance metrics per unit of risk.

Questions to ask your advisor:

- I understand that you are recommending this fund to me. What are 2 comparable funds, and why did you recommend this one rather than the other two?

- How did this fund perform during the financial crisis of 2008-2009?