This coin is part of a new series in collaboration with ABC’s Saturday extra program. Each week, the show will give listeners a ‘who am I’ quiz on the influential people who helped shape the 20th century, and we’ll post profiles for each.

Andrei Sakharov was one of the brightest scientists of the nuclear age.

In the field of theoretical physics, he has made a lasting contribution to our understanding of the universe. He also played a central role in the creation of the first Soviet hydrogen bomb in 1953. A decade later, he helped to arouse a movement towards limiting these weapons – the Atmospheric Test Ban Treaty.

Despite these accomplishments, Sakharov is best remembered today for another reason: his years as the Soviet Union’s most notorious dissident and human rights defender.

No other individual compares with Sakharov’s contribution to the global human rights “boom” of the 1970s. When he started talking about human rights in the late 1960s, the term was so esoteric as journalists Westerners have often misinterpreted it as “human rights”.

His ideas on the link between human rights and international peace won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 and helped to make human rights a central issue in the relations between the superpowers.

When Mikhail Gorbachev, then General Secretary of the Communist Party, liberalized the Soviet system in the late 1980s, Sakharov first became a leader and then a symbol of the Russian democratic movement.

A call to protect dissidents

Sakharov’s transformation from a pillar of the Soviet scientific establishment into a persecuted dissident began in 1968 with his essay “Reflections on progress, peaceful coexistence and intellectual freedom”.

In it, Sakharov argued that the world could avert the nuclear apocalypse and ecological disaster through the “convergence” of socialist and capitalist systems, which would each adopt the most human characteristics of the other.

What was needed to accomplish this historic transformation, Sakharov wrote, was intellectual freedom and the end of the repression unleashed in the USSR by the 1966 writers’ trial. Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel.

Two years later, Sakharov joined a human rights committee created by the dissident Valery Chalidze. Spurred on by Chaldize, Sakharov began to attend political trials and collaborate with others in the dissident Moscow milieu. He also started giving interviews to Western journalists and meeting visiting Western politicians.

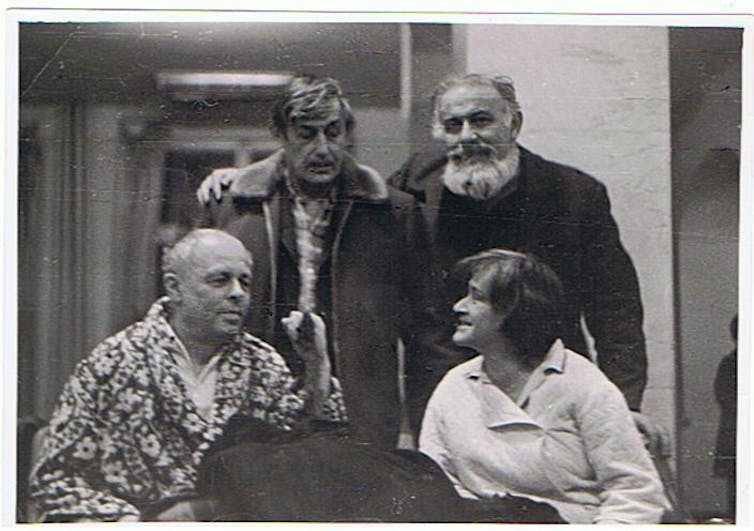

Ron Frehm / AP

The Soviet authorities retaliated in the summer of 1973. They unleashed a propaganda campaign against him which was reminiscent – by its virulence and its scope – of the Stalinist era.

Push the United States to make human rights a priority

Without being intimidated by the intensification of harassment, Sakharov threw the gauntlet at the Kremlin by addressing an open letter to the US Congress in support of a bold human rights initiative.

Under a proposal amendment to the Trade Act 1974 (called the Jackson-Vanik Amendment), a US-Soviet trade deal would be conditional on the lifting of restrictions on Jewish emigration from the USSR.

This legislation, which was repealed only in 2012, was fiercely opposed by then-US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who saw criticism of Soviet totalitarianism as a threat to improving US-Soviet relations.

In his letter, Sakharov argued that the restriction on emigration made the Soviet Union a closed society which was a danger to the world. It was a historic intervention.

As Kissinger later admitted, Sakharov’s letter “opened the floodgates.” The passage of the amendment by Congress in 1974 became a turning point in the incorporation of human rights into United States foreign policy.

It is no coincidence that Jimmy Carter, the first president to make human rights a diplomatic priority, began his term in the White House in 1977. exchanging letters with Sakharov.

Read more: Jimmy Carter’s Lasting Legacy of the Cold War

Sakharov and the Helsinki process

Sakharov’s influence on the Helsinki process, a series of East-West conferences on security and cooperation in Europe.

Launched by the signing of Helsinki Final Act in 1975, the Helsinki process was widely seen as a Western defeat as it seemed to recognize Soviet domination over Eastern Europe. Sakharov, however, saw it as an opportunity. In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize that year, he drew attention to the fact that the agreement contained

far-reaching statements on the relationship between international security and the preservation of human rights.

This idea inspired a group of dissidents, including Sakharov’s wife, Yelena Bonner, to establish the Moscow Helsinki Group (MHG), an organization dedicated to monitoring the Soviet regime’s implementation of the human rights provisions of the Final Act.

Wikimedia Commons

For nearly eight years, the MHG sent meticulous reports of Soviet violations to signatory state follow-up conferences, but its most compelling evidence was the brutal crackdown on its own members.

Thanks to these dissidents, the Helsinki Process has become what one American diplomat called “a continuous session trial” of the USSR and its Eastern European satellites.

Much of this competition focused on the fate of Sakharov himself after the Soviet regime finally decided to silence him in 1980. For speaking out against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, he was arrested and banished in internal exile.

“Our duty is in the name of Sakharov”

During his seven years of ordeal in the closed city of Gorky, Sakharov addressed the world more often with hunger strikes than with words. His treatment cast a considerable shadow on Soviet relations with the two we and Western Europe.

In response to increasing pressure, Gorbachev stunned the world in 1986 by call personally Sakharov and asking him to resume his “patriotic work”.

Read more: Explaining World Politics: The Russian Revolution

Two and a half years later, Sakharov dominated the debates of the First Congress of People’s Deputies, the Soviet Union’s first serious parliamentary experience.

With a persistence that infuriated the “aggressively obedient majority” in Congress, Sakharov challenged the constitutional supremacy of the Communist Party and urged his reformist colleagues to take the path of opposition.

They took this step the day after Sakharov’s death on December 14, 1989. A day later, the future Russian President Boris Yeltsin declared:

We have to get to the end of the path that Sakharov started. Our duty is to the name of Sakharov, to the persecution he suffered.

How we remember Sakharov today

Each year the The prestigious Sakharov Prize of the European Parliament reminds human rights defenders around the world of Sakharov’s tireless efforts to protect human rights.

In Russia, however, his legacy remains disputed. Putin’s regime marked the centenary of Sakharov’s birth in May with a commemorative coin and one statement praising Sakharov’s contribution to national security, but ignored his years as a dissident. A public exhibition intended to draw attention to Sakharov’s activism was blocked by the Moscow authorities.

This obstructionism is a tribute to the enduring importance of Sakharov to many anti-Putin Democrats, as Vladimir Kara-Murza, twice poisoned, who honor Sakharov as the embodiment of Russia’s democratic tradition.